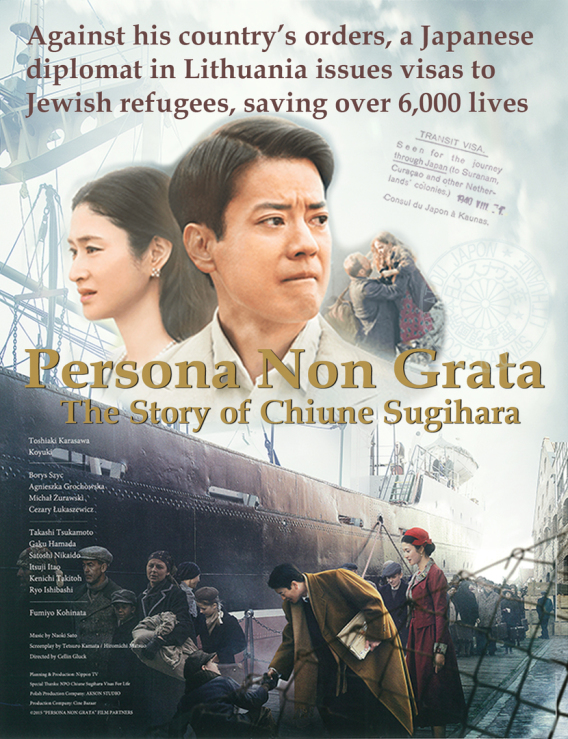

“Persona Non Grata: The Story of Chiune Sugihara”

From 7th Art Releasing – LINK TO WEBSITE

Film – Learn more about Chiune Sugihara,

by Judith Anderson

The film Persona non Grata compresses a lot of history in its first 20 minutes, taking a few dramatic liberties along the way. Here is some historical context for Sugihara’s pre-war decades.

Strategic Manchuria – Like many nations, Japan hoped to build an empire in the early 20th century. That meant conflict with Russia and China. The Russo-Japanese War (1905) ended with an unstable stalemate, with strategically-located Manchuria remaining a focus of conflicting Japanese, Russian, and Chinese interests. Though Manchuria stayed in China, the Russians, and Japanese each received concessions, including control of critically important railroads that converged on Harbin.

Harbin, the Hub – Harbin was Manchuria’s cosmopolitan city, populated by Russians, Jews, Chinese, Japanese, and other ethnic groups. A jewel in the crown of the Japanese community was the Harbin Gakuin, where students trained for careers in the Foreign Ministry. Founded in 1919 by the influential Shinpei Gotō, the Gakuin resounded with Gotō’s policies. One of these – “Military preparedness in civil garb” – defined Japan’s approach to territorial expansion: Japan’s matchless civilization would camouflage its military muscle, making it an attractive colonial master.

“Russia hand” – As a student at Harbin Gakuin in 1919, Sugihara absorbed Gotō’s views and became an expert on Russian issues and language. During the next two decades, largely based in Manchuria, he worked variously for the Japanese intelligence services, Foreign Ministry, and military. They all needed information about the Soviets, for disparate reasons. Serving these different employers, Sugihara came face to face with the contradictions inherent in “Military preparedness in civil garb”.

“Russia whisperer” – In September 1931, the Kwantung Army (Japan’s army in Manchuria) staged a railroad sabotage, the “Mukden Incident”, as an excuse for military takeover. In short order, Manchuria became a Japanese puppet state, “Manchukuo”. However, the Russians still controlled a major rail line through Harbin, the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER). In the mid-1930s, the Japanese weighed two possibilities for getting control of the CER. The military favoured direct seizure, risking a war with the Soviets. Civil authorities preferred to buy the railroad, but the Soviets named a high price and stealthily began to remove the best CER equipment to Soviet territory during the negotiations. To save the negotiations, Sugihara was given a complex, perilous assignment – to assess the value of the CER and to document equipment inventories. He worked squarely in the nexus of all the conflicting interests. His thorough reports on the CER and exposure of the equipment theft enabled Japanese civil authorities to keep the Russians at the table, where they finally settled on a lower price. Sugihara’s efforts likely averted a major military conflict with the Soviets, but the internal tensions between “military preparedness” and “civil garb” remained unresolved.

Russian love interest – From 1924 to 1935 Sugihara was married to Klaudia Semionovna Apollonov, a Russian who, like many in Harbin, had fled the Revolution. It’s possible that she was an “operative”.

Some recommended reading –

In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked his Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews From the Holocaust, by Hillel Levine (1996)

The Fugu Plan: The Untold Story of the Japanese and the Jews During World War II, by Marvin Tokayer (2012)

I Have My Mother’s Eyes: A Holocaust Story Across Generations, by Barbara Ruth Bluman (2009)

Learn about the people who received Sugihara’s visas – For detailed information on the 2100 Sugihara visa recipients, compiled by George Bluman and Akira Kitade, see http://www.math.ubc.ca/~bluman/ChiuneSugiharaLists.html